YOM HA SHOAH 2023 by Raphael ben Levi

On 27 January, 1945, Auschwitz-Birkenau, the largest Nazi Concentration Camp was liberated. What was the impact of the Holocaust upon those who survived the ravages of Hitler’s planned extermination of Europe’s Jews, and what were the effects upon the succeeding generation? I never find talking about this easy. The memories are complicated. Allow me to explain.

Hitler did not succeed in taking my parents lives, but he changed them in ways that lingered on in us their children. Our world was tainted with a woundedness that other Jews residing in safe havens were mercifully spared. For several years, within the silent etiquette of post-war Britain, many survivors were branded as anomalies and set apart from the pack. Dysfunctional behaviour and cultural eccentricities, however well tolerated outwardly, was considered a cause of great concern within Jewish communities due to the fear that the surviving Holocaust casualties of war “with the foreign accents” would only at the end of the day reinforce anti-Semitism that was always simmering just under the surface of that ‘stiff upper lip.’ Hitler had succeeded in ways he could never possibly have imagined.

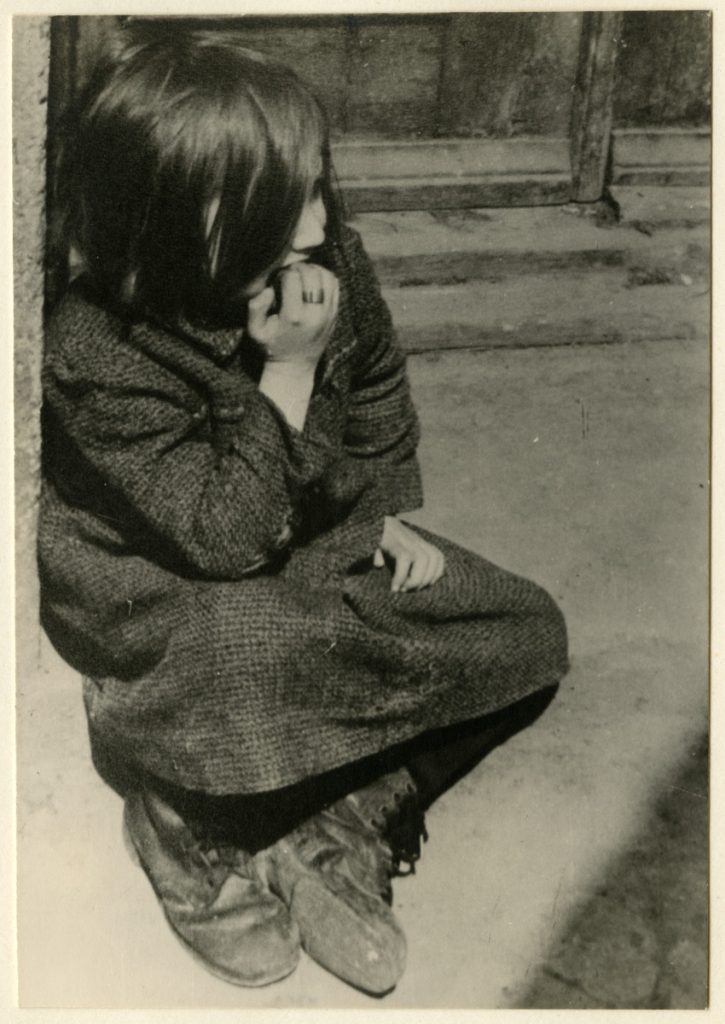

At home, we were surrounded by relics influenced by tortured mind sets. My parents subconsciously downloaded much of their emotional baggage upon those closest to them – their children. These things were messy because they invaded personal territory and crossed boundaries as we became trapped within our parent’s nightmare. They relived the trauma of their memories as a survival mechanism; yet by doing so, it was like peering over the precipice into an inferno. Ignorance is never bliss, because the past has a way of catching up with you. Our identities became mutilated by deep scars inherited from parents who experienced the unthinkable. One person explained it like this:

“Survivors were generally older than escapees and had slightly more control over their fates. They relied upon qualities within themselves that saved their lives. Torture, abuse, and loss taught survivors to be cunning, enduring, or even complicit – anything to live another day. Yet, escapees were children and, therefore, pure victims. If my mother had been a (Holocaust) survivor, maybe she would be grateful and could have felt each day as a gift, every year as a mission. Yet, as an escapee, she feels she doesn’t deserve to live. For that matter, she’s not sure she wants to, not without her parents. Her understanding is stuck in a 12-year-old’s broken heart. All she can know is that her mother and her Motherland abandoned and rejected her, and that’s what she can never escape.”

She used a shocking example by way of illustration:

“When I was ten and our family returned from an unusual, delightful weekend of downhill skiing, I saw the limitations of my mother’s happiness. When we got home, she locked herself in the bathroom and sobbed wildly from behind the door. ‘What’s wrong?’ my father asked as he knocked. ‘Didn’t we have a good weekend?’ She refused to open the door but yelled from what seemed like the other side of a gulf: ‘Yes, we had a wonderful time. I don’t think I will ever have a day like this again. I have never been so happy and I doubt if I’ll ever be again. I don’t deserve it.’”

Asking questions is natural, but are they the right ones that can lead us to a better understanding of ourselves, greater self acceptance and importantly, healing and restoration? This has been the dilemma facing 200,000 children of Holocaust survivors world-wide who became the post-Holocaust generational anomaly.